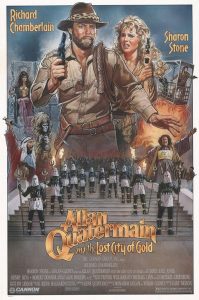

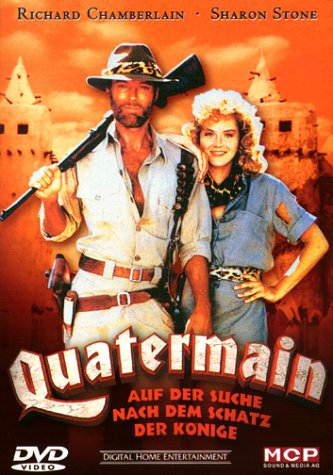

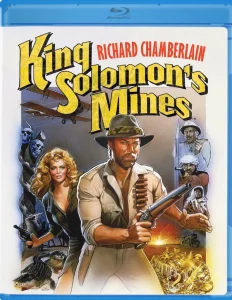

King Solomon’s Mines (1985)

For a generation raised on the exhilarating archaeological escapades of Indiana Jones, any film offering a similar blend of peril, pulp, and exotic locales was eagerly consumed. The 1985 iteration of King Solomon’s Mines perfectly captured this appetite, serving as an unofficial gateway into the long cinematic history of H. Rider Haggard’s iconic great white hunter, Allan Quatermain.

Before delving into the Cannon Group’s famously bombastic 80s effort, it’s worth reviewing Quatermain’s earlier screen incarnations:

Allan Quatermain (1919)

A silent short screened on All Hallow’s Even. Though considered lost, author H. Rider Haggard himself noted in his diary that “It is not at all bad, but it might be a great deal better.” Stills are the only known surviving evidence.

King Solomon’s Mines (1937)

The first acknowledged sound version. A largely enjoyable adventure, though the presence of surprising musical numbers adds a distinctive and perhaps jarring flavour compared to later versions

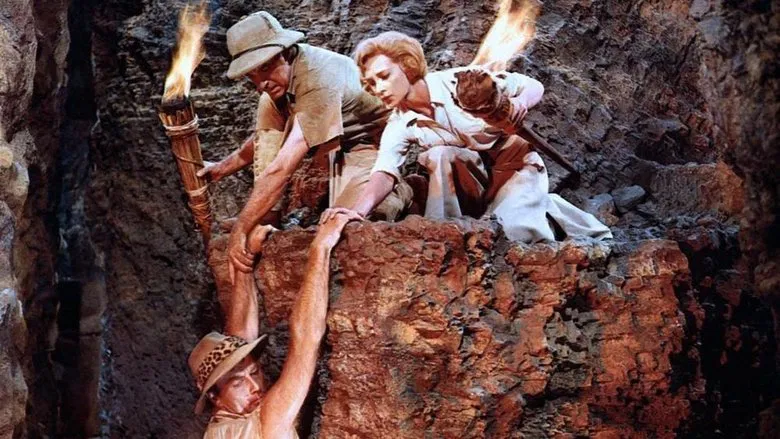

King Solomon’s Mines (1950)

The Definitive Version. MGM’s sumptuous production, featuring stunning Technicolor and location filming, set the standard. The palpable on-screen chemistry between Deborah Kerr and Stewart Granger is as legendary as their reported off-screen drama. For purists seeking the most classic and beautifully shot adaptation, this remains essential viewing.

Watusi (1959)

Essentially an unofficial sequel to the 1950 version, the narrative pivots to Allan’s son, Harry Quatermain (played by George Montgomery). Funnily, it shares a World War I setting with the later 1985 version, making it a favourite despite its nature as a direct cash-in on the success of the Granger/Kerr hit.

King Solomon’s Treasure (1979)

A low-budget misfire that attempted to capitalise on the source material. A truly terrible experience, memorable only for its spectacularly bad elements, such as giant, unconvincing crabs and the hapless presence of David McCallum. It serves as a perfect, albeit painful, example of the struggles of British cinema toward the end of the 1970s.

This brings us to the infamous 1985 adventure from the legendary, and often ludicrous, Cannon Group. When you see the Cannon logo, you know exactly what to expect: a high-octane, low-budget, often schlocky brand of adventure—a far cry from a “flawless experience,” but exciting nonetheless!

Few films hold ‘guilty pleasure’ status quite like this one. In the summer of ’89, fueled by Last Crusade fever, I was scouring video shops for a copy of Temple of Doom to sit alongside my well-worn TV recording of Raiders. Temple was nowhere to be seen, but King Solomon’s Mines was staring back at me. The owner’s reaction told me everything I needed to know: when I offered to buy the film and its sequel, he just gave them to me, well, he practically shoved both it and the sequel into my hands for free. Clearly, the shelf space was worth more to him than Quatermain’s adventures, but I went home feeling like I’d found buried treasure.

Starring Richard Chamberlain (then famous for Dr. Kildare and The Three Musketeers) and a pre-stardom Sharon Stone, the film was clearly designed to siphon some of the massive box-office success of the Indiana Jones franchise. Chamberlain, though not holding a candle to Harrison Ford’s iconic swagger, makes a thoroughly enjoyable and game effort in the lead role, embodying a somewhat dapper and visibly enthusiastic version of Quatermain. I always have a huge smirk at his ongoing “I’ve got it!” yell and his reaction to “The breasts of Sheba.” Stone, reportedly difficult to work with on set, is still magnetic, showcasing the beauty and raw star power that would later make her famous, even if her on-screen persona hadn’t yet been fully honed.

There is not one, but two villains! John Rhys-Davies (ironically, a veteran of Raiders of the Lost Ark) and Herbert Lom are excellent as the dual villains, a sadist turk called Dogon and the no nonsense Nazi Colonel Bockner. Their infectious, yet non-offensive, hate relationship and constant bickering provide wonderful comic relief, yet these two professionals still manage to infuse a healthy dose of villainous menace. The supporting cast delivers pure pulp fun.

The true star of the film is indeed the magnificent score by Jerry Goldsmith. His music is as rousing and instantly memorable as John Williams’s Raiders March. Every time Quatermain performs a minor heroic act, the theme blasts out, injecting the film with a genuine sense of heart, joy, and grand adventure. It’s a remarkable feat that a score of this quality was attached to such a production, effectively masking many of the film’s flaws.

The moment the Jerry Goldsmith score begins, the film hooks you. However, survival of the rest of the film is not a given, unless you embrace the absurd. From the very first lines “It’s a jungle out there” and “Here we are in beautiful, downtown Tongola”, the movie proudly announces that it is not to be taken seriously. This pervasive sense of self-aware, cheap silliness is the film’s strength, preventing the low-budget effects from undermining the overall enjoyment.

King Solomon’s Mines (1985) is the antithesis of a perfect movie, and arguably did more to create a high-camp adventure reputation for Haggard’s novels than any serious literary appreciation. However, it is an undeniable amount of fun. J. Lee Thompson was no stranger to schlock, and he handled this brand of nonsense with seasoned expertise. While his later career admittedly descended into much shoddier territory, he still possessed the veteran’s touch required to keep the audience thoroughly entertained.

Despite its schlocky nature, the film performed well enough at the box office to merit the sequel. Luckily, they filmed one back to back. One day I hope for a boutique Blu-ray company to pick up the film, clean it up, and potentially include the any scenes omitted from the final cut and this is a sentiment shared by many fans of 80s B-cinema. There must be a wealth of material to dig into for a definitive, high-definition version of this treasured guilty pleasure.

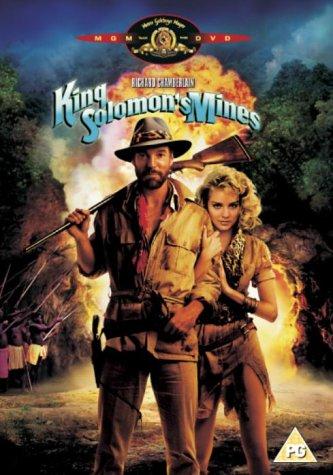

While Germany and France have both received superior Blu-ray releases of King Solomon’s Mines over the US release. UK fans currently have to turn to the import market for a high-definition experience.

If you aren’t ready to import, the MGM DVD remains a solid alternative with respectable picture quality. Conveniently, the sequel comes in a similarly designed package, making for a handsome set on the shelf.